Svelte - Tutorial Walkthrough, Part 4

Svelte Tutorial, Part 4

This is the 4th post in a series walking through Svelte’s online tutorial. In the first post we covered Introduction, Reactivity, and Props. The second post explored Logic and Events. The third post dove deeply into Bindings.

Today, we will explore Lifecycle and Stores!

Lifecycle

The Svelte Lifecycle represents the different stages a Svelte component undergoes as it is rendered in the browser. While Svelte hides this complexity behind the compiler, knowing how it works is useful for a few reasons:

- Unexpected behavior may occur if your code is doing certain things (eg, network calls) at the incorrect times in the component lifecycle

- Lifecycle hooks provide a better understanding of how Svelte builds the DOM.

As you build your Svelte ninjitsu, you must deepen your familiarity with the underlying framework. Over the long haul, this will increase your coding power. Lifecycles are a great example where deeper understanding will multiply your abilities.

onMount

The first function covered is onMount, which executes after the component is first rendered to the DOM. According to the tutorial, this is the most important Lifecycle function.

One use case for onMount is when executing networking calls using Javascript’s fetch. While you could make this call directly in the ‘script’ tag of your component, that won’t work correctly if you’re using server side rendering (SSR).

Here’s a quick example of using onMount:

onMount Example

<script>

import { onMount } from 'svelte';

let starWarsCharacters = [];

onMount(async () => {

const res = await fetch(`https://swapi.dev/api/people`);

starWarsCharacters = await res.json();

});

</script>

{#each starWarsCharacters as starWarsCharacter, i}

// Render Wisely

{/each}

onDestroy

Svelte’s onDestroy hook performs cleanup, preventing memory leaks when the runtime destroys a component. The example provided in Svelte’s tutorial demonstrates using onDestroy to clean up after a setInterval function.

This is an important thing to consider with JS UI development, especially as your app grows larger. Memory leaks can kill a site’s performance, and it’s not always apparent when they exist. The app still works with memory leaks, and usually doesn’t suffer until under heavier load. That lulls people into not thinking about some of the deeper and more complicated problems that can occur. Here’s a good article going deeper on that topic.

beforeUpdate and afterUpdate

Svelte provides beforeUpdate and afterUpdate hooks that will trigger before and after the DOM is synchronized with your data. In the words of the Svelte tutorial, “they’re useful for doing things imperatively that are difficult to achieve in a purely state-driven way, like updating the scroll position of an element.” To my ears, that means “lots of things can go sideways with HTML and DOM positioning/rendering - before/after update gives you hooks to cobble together fixes”.

In a way, these might be considered “backdoors”. While slightly hacky, these are sometimes necessary. It’s really hard to get everything in a complex framework to work correctly all the time, especially across different browsers and versions. Sometimes, you need a backdoor.

tick

Svelte’s tick is another “back door” into the Svelte lifecycle. Svelte will batch updates to the DOM in order to improve efficiency (using microtasks). Sometimes you have code you don’t want to execute until this synchronization has completed. The “tick” function allows you to effectively wait for the next refresh before executing logic.

The tutorial has a good example you should look into, but in a nutshell, it looks something like this:

tick Example

<script>

// Do lots of things

await tick(); // This will not return until the next Svelte batch update occurs

// Do things which require the latest state to work correctly

</script>

Stores

Ahhh….Stores. For me, this was where Svelte made the leap from “interesting widget framework” to “something I can use to build an actual application”. Stores allow you to share data across unrelated components, as well as with non-Svelte Javascript modules. To my naive understanding, Stores are to Svelte what Redux is to React.

Writeable Stores

In their simplest form, Stores achieve the following:

- Store a value

- Allow value to be updated (via “update”)

- Allow value to be set (via “set”)

Here’s a brief example:

stores.js

import { writable } from 'svelte/store';

export const name = writable('');

Component.svelte

<script>

import { name } from './stores.js';

function setToBilly() {

name.set('Billy');

}

function addExclamation() {

name.update(n => n + '!');

}

let name_value;

const unsubscribe = name.subscribe(value => {

name_value = value;

});

</script>

<button on:click={setToBilly}>

Name Him Billy

</button>

<button on:click={addExclamation}>

Yell Louder

</button>

<div>{name_value}</div>

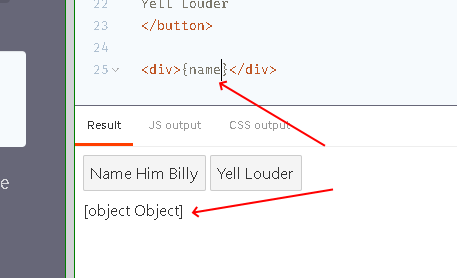

One issue I encountered at first was the inclination to bind to the writable store itself. There’s an important distinction here - the store is the container for the value, but is not the value itself:

Auto Subscriptions

With Svelte’s auto subscriptions, you can bind directly to the Store, and leave much of the boilerplate code behind. This is enabled by using the “$” operator, like the following:

Component.svelte

<script>

import { name } from './stores.js';

function setToBilly() {

name.set('Billy');

}

function addExclamation() {

name.update(n => n + '!');

}

</script>

<button on:click={setToBilly}>

Name Him Billy

</button>

<button on:click={addExclamation}>

Yell Louder

</button>

<!-- Binding directly to Store -->

<div>{$name}</div>

Not only does this get rid of some boilerplate logic, it also eliminates a potential memory leak. When you directly subscribe to a writeable store, you are passed back the unsubscribe function. If you don’t invoke that, a memory leak occurs:

MemoryLeakComponent.svelte

<script>

import { name } from './stores.js';

let name_value;

const unsubscribe = name.subscribe(value => {

name_value = value;

});

</script>

This can be addressed by using the onDestroy lifecycle hook, like the following:

NoMemoryLeakComponent.svelte

<script>

import { onDestroy } from 'svelte';

import { name } from './stores.js';

let name_value;

const unsubscribe = name.subscribe(value => {

name_value = value;

});

onDestroy(unsubscribe);

</script>

But by using the “$” approach, you can avoid that boilerplate altogether.

Readable Stores

Readable Stores provide a centralized Store that consumers can’t update - it merely provides read-only values. The example in the Svelte tutorial features a readable store that maintains the current time. They also mention you may want to use a readable store to contain the current mouse position.

Implicit in their examples is that you’d want to use setInterval method to periodically enable a refresh of your readonly store (via the “set” callback). Quickly googling for other examples didn’t reveal any other use cases.

Derived Stores

Derived Stores offer the capability of building a store that is derived from another store. This one gets a little more involved, and the Svelte API documentation provides more details. In an nutshell, you can build a derived store from any number of other stores. Additionally, it features overrides that take a callback function as a parameter, allowing you to set the derived value in an async fashion.

Custom Stores

Custom Stores allow anything with a correctly implemented “subscribe” method to be a store. This means that you can export a function that encapsulates “setting” functionality, and simply allows a consumer to subscribe to it. This ensures that consumers won’t ever do “bad things” with your store, and you have more control over how it can be used.

The tutorial illustrates this by building on its example in writeable stores, but instead of directly exporting the store, it exports an object that contains the store.

Building on our previous example, we could update our “name” store to provide better encapsulation:

CustomStore.js

import { writable } from 'svelte/store';

function createName() {

const { subscribe, set, update } = writable('');

return {

subscribe,

setToBilly: () => {

set('Billy');

},

addExclamation: () => {

update(n => n + '!');

}

};

}

export const name = createName();

Features like this both demonstrate to me the power of functional programming in Javascript, and how creatively it can be used. Cool beans.

Store Bindings

Writeable Stores can be bound to components the same way as standard variables. This offers a powerful mechanism for allowing input controls to update the values contained in your store:

StoreBinding.svelte

<script>

import { name } from './stores.js';

</script>

<input bind:value={$name}>

<div>{$name}</div>

Summary

So there you have it, Lifecycle and Stores. Note, we are only scratching the surface here, and are getting into more complicated territory. Reading these topics gives you familiarity with the framework. However, in order to become proficient, you’ve got to roll up your sleeves and start coding. I’d recommend doing so now - start with a simple idea, use onMount to retrieve data, and use a Store to share it around.

The Svelte Ninja will always be with you. If you’re like most, you will occasionally stumble. Episodes will occur where the STUPID thing should JUST WORK, and ISN’T!

Maintain calm, and deepen your breath. With patience, you will overcome obstacles like this, and the Svelte Ninja will sagely nod his head with silent approval. He knows this road as well, and has travelled it. You will reach your destination!

Thoughts & Notes

- I use Visual Studio Code for most of my work, these posts included. I finally started spell checking my posts last week (after discovering some embarrassing spelling errors in my published work). At first, I copied everything into a Google Doc and used its spell checker. However, I quickly remembered that VS Code has a huge library of extensions, and looked for a spell checker. And lo and behold, there’s one here! Hopefully this will prevent future spelling mistakes…